A lot has been written about some core WPF design patterns - particularly the MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel) pattern and the comprehensive data-binding and data-template support that makes it work so well. However, those patterns by themselves aren’t sufficient to create a full WPF application.

I thought it would be worth looking into other patterns that work together to form one approach to the creation of a comprehensive application - this is the first post in what may become a series.

Updated 23/8: Added some diagrams and updated the wording of the Motivation section to add clarity.

Related Posts

I posted a followup to this post called “WPF Design Patterns: Window Manager”.

Event Aggregator

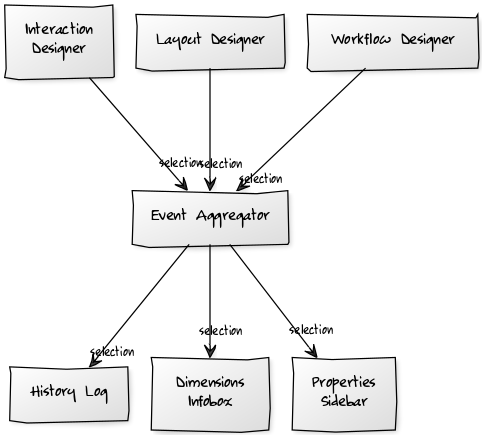

The event aggregator allows widely disparate parts of the application to communicate with each other in a decoupled fashion. Instead of each component needing to know about the others, they take a simple dependency on a centralised message broker that dispatches messages as required.

Motivation

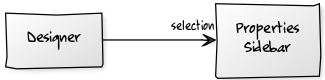

Imagine your application includes a sidebar that allows for detailed configuration of the current selection - think of the Properties sidebar found in Visual Studio, or the Object Inspector found in Dephi.

When the selection changes in your designer, you want this sidebar to update and show the appropriate detail for the new selection.

As long as you have only one source of selection, you could wire the two components directly together - but things start getting very messy if you have multiple ways for different things to become selected. Wiring all of the components directly to each other becomes burdensome, a kind of combinatorial explosion of tight coupling.

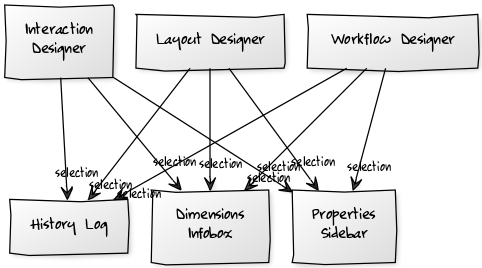

Consider what happens when your application grows - now you have three different kinds of designer, each with a current selection, as well as multiple sidebars for viewing properties, dimensions and the modification history of the selected element.

Instead, the event aggregator pattern allows you to define a simple message - say, SelectionChangedMessage - that

can be sent by any component changing the selection. The configuration sidebar can subscribe to that message and react

appropriately, reguardless of the message origin. Better yet, adding a new component - whether a selection publisher

or a selection consumer, requires adding just one new link.

Show me the code

Here’s a simple IEventAggregator interface that I’ve used to good effect in a bunch of different applications:

/// <summary>

/// Functionality interface for an Event Aggregator

/// </summary>

public interface IEventAggregator

{

/// <summary>

/// Send a message

/// </summary>

/// <remarks>

/// Sends the message and waits for processing on the UI thread before returning.

/// </remarks>

/// <typeparam name="T">Type of the message</typeparam>

/// <param name="message">Message to send</param>

void SendMessage<T>(T message);

/// <summary>

/// Post a message

/// </summary>

/// Posts the message for later processing on the UI thread, returning immediately.

/// <typeparam name="T">Type of the message</typeparam>

/// <param name="message">Message to send</param>

void PostMessage<T>(T message);

/// <summary>

/// Register a message handler

/// </summary>

/// <param name="eventHandler">Message handler to add.</param>

/// <returns>Registered delegate</returns>

Action<T> RegisterHandler<T>(Action<T> eventHandler);

/// <summary>

/// Unregister a message handler

/// </summary>

/// <param name="eventHandler">Message handler to remove.</param>

void UnregisterHandler<T>(Action<T> eventHandler);

}The EventAggregator implementation (shown at the end of this post) is always configured as a singleton through a

dependency injection framework and provided to the various components through a parameter of their constructor.

For example, the ViewModel for a sidebar component as described above would hook into the event aggregator for

processing of a SelectionChangedMessage by using code like the following:

/// <summary>

/// Initializes a new instance of the PropertySidebarViewModel class

/// </summary>

/// <param name="eventAggregator">

/// Reference to our global Event Aggregator

/// </param>

public PropertySidebarViewModel(

IEventAggregator eventAggregator)

{

mEventAggregator = eventAggregator;

// Register our method SelectionChangedHandler as a handler

// for the SelectionChangedMessage message

eventAggregator.RegisterHandler<SelectionChangedMessage>(

SelectionChangedHandler);

}

private void SelectionChangedHandler(

SelectionChangedMessage message)

{

// Handle the SelectionChanged message

}

private readonly IEventAggregator mEventAggregator;Tip: Message Naming

Applications using an event aggregator often end up with a fairly large set of distinct messages - using a simple

naming convention to ensure that all messages are easily recognised is invaluable. A simple suffix of Message on all

the classes is direct and easy, though some use the suffix Event instead, on the basis that the pattern is called

Event Aggregator.

Ensuring the rest of the name is clear is also important. A message called SelectionChangeMessage is ambiguous - does

it indicate that the selection is being changed, or that the selection has been changed. One approach is to rely on

language tenses - the current tense SelectionChangingMessage for a selection that is currently being changed and the

past tense SelectionChangedMessage for afterwards. Another approach is to explicitly prefix messages for clarity -

BeforeSelectionChangeMessage, OnSelectionChangeMessage and AfterSelectionChangeMessage are little prone to being

misunderstood.

Tip: Handler Naming

It is equally important to be clear with the names used for the methods that handle each event.

One effective approach is to base the name of the method on the name of the message, but with a different suffix.

The method SelectionChangedHandler() is therefore going to be linked to the message SelectionChangedMessage,

the method SelectionChangingHandler() the message SelectionChangedMessage and so on.

As a bonus, using an approach like this makes it possible to easily search for all handlers for a particular message.

Tip: Use a Folder

With anything more than a trivial number of messages, keepting them together in a distinct folder and associated namespace can be useful, as it helps to prevent them from overwhelming more important classes.

Tip: Use Immutable classes

Where possible, use immutable message classes, especially for use with the “fire and forget” Post method used for

asynchronous delivery of the messages. Given that the order of message delivery is essentially uncontrollable, a message

that gets modified enroute by one consumer might have unwanted side effects that are difficult to debug.

/// <summary>

/// Domain message sent when the current selection has been changed.

/// </summary>

public class AfterSelectionChanged

{

/// <summary>

/// Reference to the instance that is now the current selection

/// </summary>

public object Selection { get; private set; }

/// <summary>

/// Initializes a new instance of the SelectionChangedMessage class.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="selection"></param>

public AfterSelectionChanged(object selection)

{

Selection = selection;

}

}One exception would be for “permission” events that allow event handlers to cancel an operation before it starts.

The classic approach for implementation is to expose a read/write Boolean property Cancelled which consumers can

set to true. The problem is that any other consumer can set it to false and override the cancellation. A

better approach is to have a read/only IsCancelled property along with a separate method Cancel() which prevents

misuse.

More Code

Here is a full implementation of the EventAggregator class for use in a WPF application. It’s dependent on the

presence of a synchronisation context to work properly - so a simple transplant into non WPF context may not go

smoothly.

/// <summary>

/// Central event dispatcher used to send application messages to registered handlers

/// </summary>

public class EventAggregator : IEventAggregator

{

/// <summary>

/// Initializes a new instance of the EventAggregator class.

/// </summary>

public EventAggregator()

{

mSynchronizationContext = SynchronizationContext.Current;

}

/// <summary>

/// Send a message instance for immediate delivery

/// </summary>

/// <typeparam name="T">Type of the message</typeparam>

/// <param name="message">Message to send</param>

public void SendMessage<T>(T message)

{

if (message == null)

{

return;

}

if (mSynchronizationContext != null)

{

mSynchronizationContext.Send(

m => Dispatch<T>((T)m),

message);

}

else

{

Dispatch(message);

}

}

/// <summary>

/// Post a message instance for asynchronous delivery

/// </summary>

/// <typeparam name="T">Type of the message</typeparam>

/// <param name="message">Message to send</param>

public void PostMessage<T>(T message)

{

if (message == null)

{

return;

}

if (mSynchronizationContext != null)

{

mSynchronizationContext.Post(

m => Dispatch<T>((T)m),

message);

}

else

{

Dispatch(message);

}

}

/// <summary>

/// Register a message handler

/// </summary>

/// <param name="eventHandler">Message handler to add.</param>

public Action<T> RegisterHandler<T>(Action<T> eventHandler)

{

if (eventHandler == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("eventHandler");

}

mHandlers.Add(eventHandler);

return eventHandler;

}

/// <summary>

/// Unregister a message handler

/// </summary>

/// <param name="eventHandler">Message handler to remove.</param>

public void UnregisterHandler<T>(Action<T> eventHandler)

{

if (eventHandler == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("eventHandler");

}

mHandlers.Remove(eventHandler);

}

/// <summary>

/// Dispatch a message to all appropriate handlers

/// </summary>

/// <typeparam name="T">Type of the message</typeparam>

/// <param name="message">Message to dispatch to registered handlers</param>

private void Dispatch<T>(T message)

{

if (message == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("message");

}

var compatibleHandlers

= mHandlers.OfType<Action<T>>()

.ToList();

foreach(var h in compatibleHandlers)

{

h(message);

}

}

/// <summary>

/// Storage for all our registered handlers

/// </summary>

private readonly List<Delegate> mHandlers = new List<Delegate>();

/// <summary>

/// SynchronizationContext used to transition to the correct thread

/// </summary>

private readonly SynchronizationContext mSynchronizationContext;

}A nice side effecct of this implementation is the thread afinity - messages are always delivered

on the UI thread, reguardless of the thread of origin. Using the EventAggregator to Post

asynchronous UI updates from a background thread doing some bulk processing is both clean and

performant.